By Grady Short

Every year the college admissions process gets harder. Acceptance rates drop, expectations go up, and students compete more fiercely than ever in their academic and extracurricular pursuits — an issue that MIHS’s culture of fierce competition only exacerbates. It comes as no surprise, then, that some students attempt to take shortcuts when trying to look their best for admissions departments.

Perhaps the most common method is to obtain a leadership position in a club or organization without actually following through with the required responsibilities. Take, for instance, the Junior Statesmen of America (JSA), a club which barely met at all during the past school year. Running and organizing this club took little to no effort, but the students who led it still got to put down this impressive-sounding position in their college applications. Since most applications and admissions departments do not require any form of verification for extracurricular activities, students have the ability to lie or stretch the truth with relative ease.

And it’s not just the JSA, which is now being built up into a more legitimate club according to president Mary Rose Vu. In a particularly striking case, one of the school’s largest organizations, the National Honor Society (NHS), requires little effort from its members despite the high standards suggested by its name.

This organization, which is based around community service and academic success, requires that its members maintain a minimum unweighted GPA of just 3.5. An attempt to increase the minimum GPA to 3.75 last year resulted in significant parental pushback, according to a member of the society familiar with this policy. Members must also participate in 10 hours of community service each semester, including at least one NHS-sponsored project. Other subject-specific honor societies require even less — the French Honor Society requires just two hours of community service per semester, and the recently formed Tri-M Music Honor Society has a minimum GPA of 3.0 in music classes, with a minimum of just 2.0 for non-music subjects.

The National Charity League (NCL), another popular service organization on Mercer Island, sets a similarly low bar for its members. “We spent more time going to [chapter meetings] than doing actual community service,” said a former member, who went on to describe the league as “parent-dominated” and “cliquey.” Because of its status and legitimacy as a national service organization, rather than the actual charitable work that members partake in, the NCL remains popular among students at MIHS.

Looking at the master list of clubs at MIHS, one might be surprised by the quantity of ASB-approved clubs which have no noticeable presence in the school. The average student might very well be surprised to learn that MIHS has a Sailing Club, Adventurer’s Club, and Poiesis Club. Starting one’s own club or organization is a big draw for students looking to gain an edge in the admissions race, and in some cases drives students to found or lead clubs but simply fail to follow through, resulting in an unstable club scene which is constantly in flux.

This trend disincentivizes students from joining clubs and organizations which require more effort, since the end result on a résumé or activities list will look the same. Another phenomenon in this vein is the increasing number of captains or leaders that sports and clubs have; in most sports and activities at MIHS the position of captain is no longer reserved for one or two members with special leadership skills, but is now doled out to more students due to the edge it provides in college admissions.

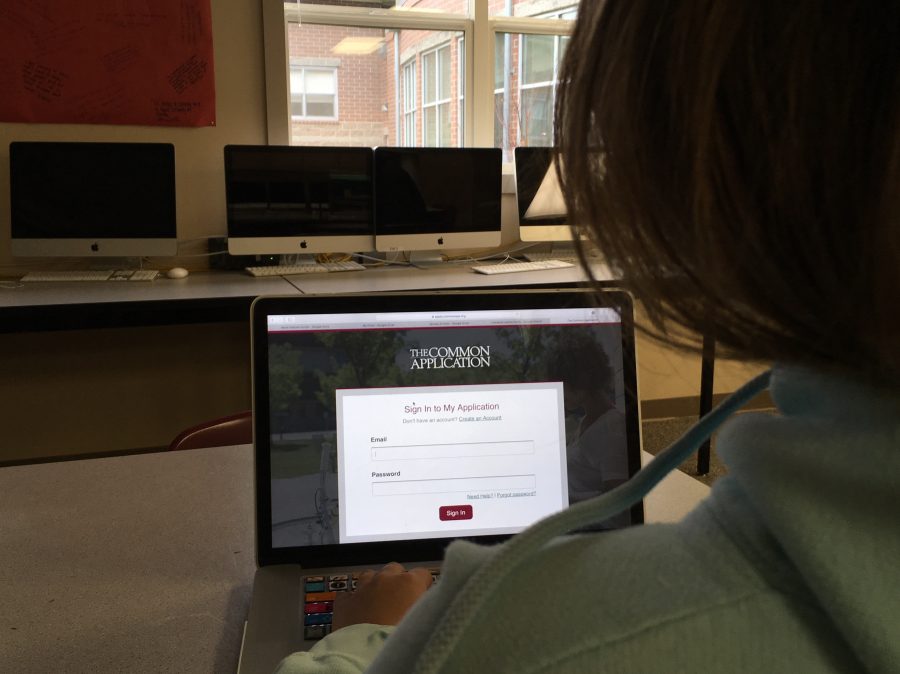

Piling on low-effort, big-name extracurricular activities comes in handy when competing with other students in the college application process. Photo by Grady Short

All this is a direct result of the immense pressure on students to succeed academically, but where does this pressure come from? Parents certainly factor in; the school district has received threats of legal action from parents over perceived slights within MIHS’s institutions in the not-so-distant past. The ever-increasing competitiveness of the college admissions process plays a large role too; seeing acceptance rates of five or ten percent at selective colleges motivates students to do anything to get in, including distorting the truth or participating in low-effort, big-name activities.

MIHS boasts a large amount of clubs and motivated students, but is weighed down by students looking to obtain an entry in their résumé rather than a committed club experience. One possible approach to creating a healthier club scene would be for the ASB and club leaders to toughen up the requirements for a club to be considered legitimate. It would also redirect the energy students currently use padding their résumés towards more constructive pursuits. But for now, the academic culture and club requirements at MIHS incentivize students to participate at a bare minimum — enough to look good for admissions officers, but not enough to create strong, productive student organizations.