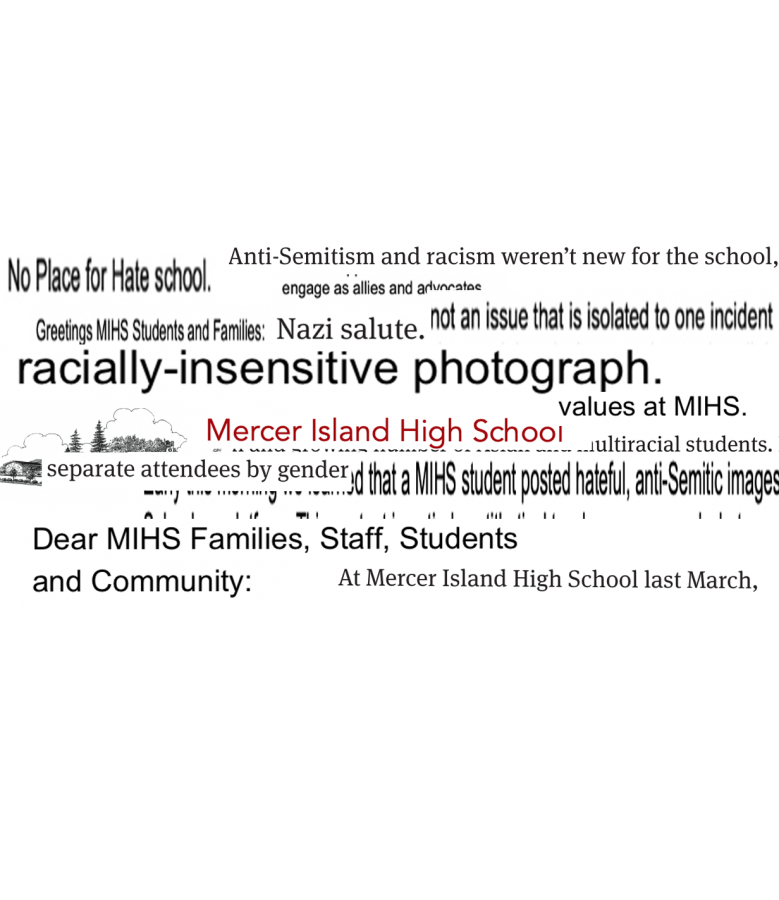

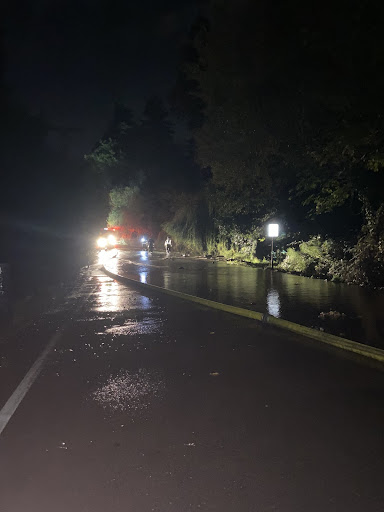

This September, a series of offensive posts were published on a public MIHS Schoology page.

The posts contained both anti-Semitic photos as well as content referring to the Japanese imperial flag–a harmful symbol–unfortunately, both anti-Semitism and the Japanese imperial flag have a history at MIHS. Students at the high school took to social media to share their disgust and dismay at the posts. A senior, who wished to remain anonymous, was especially frustrated that the Japanese imperial flag imagery had yet to be officially acknowledged as of September 19.

For many, the flag is a grim reminder of the horrors and human rights atrocities committed by the Japanese imperial regime throughout Asia from the mid-19th century until the end of World War II.

Principal Walter Kelly responded on behalf of the school the next morning, condemning the posts. “This content is counter to everything that we strive to be as a school and community,” Kelly said.

Superintendent Donna Colosky also sent out an email to parents detailing how the district will address hate in MISD schools. She notes multiple efforts that had been implemented in the past, such as MIHS’s designation as “No Place for Hate” school, a new social justice group now known as the Student Group on Race Relations and a new grant that will be used to “implement inclusionary practices at all levels”. In the future, MISD plans to continuously review literary curriculum and to “[focus] on breaking down and removing systemic barriers”.

However, @studentsofmi, an anonymous student-run Instagram account, made it clear that September’s posts were no isolated incident. Created in July, the account posts anonymous submissions from Mercer Island students who have experienced racism, antisemitism, or other forms of bigotry.

One student’s submission to @studentsofmi highlights that “the amount of holocaust ‘jokes’/Jewish stereotypes/swastikas [they] see written on desks/etc is [expletive] disturbing. Even after making the news two years ago and [the school gained] a reputation for being anti-semitic […they] still see/hear [expletive] like this weekly.”

In multiple other posts on the same account, students mentioned that when they had encountered hateful comments, they were met with indifference from their peers and teachers.

For instance, a student recounted that while discussing the internment camps used to forcefully incarcerate Japanese-Americans during WWII, “multiple kids in [their] class [defended] Japanese internment camps. The teacher supported them and completely overlooked [the offending comments].”

There is a distinct, ongoing issue with bigotry and discrimination coming from students and faculty in our learning environments. This begs the question: what is our school community going to do about it? Will the ambitions, which lacked a clear plan of action, outlined by the district be enough to combat this bigotry and discrimination?

What the district has committed to doing in the past is not enough. Typically, the response to hateful incidents consists of an apology from the district along with a promise to “do better”, followed by a discussion in class along with an assembly and video.

In response to September’s incident, MISD officials stated that they will continue their work to address such hate. The end of an email sent to parents days after the posts, speaking on behalf of the district, says that “this latest incident only magnifies the importance of this work”. The response to this particular incident is nearly identical to previous responses.

Hateful incidents such as these are not caused by one component of our educational community nor should blame be placed on any particular component. However, we also must acknowledge that district and school officials have the most power when it comes to responding to discrimination.

When we look to district officials, where are the fundamental changes being outlined since, undoubtedly, discriminatory incidents are a recurring and common issue? If we do not enact specific and significant change in response to this incident, then we cannot expect these incidents to stop.

“The people we look to in our community need to do a better job at realizing that there is a problem […] you have to do more, push out resources for people to educate themselves with,” senior Keishani Griffin said. “We need people to get out of their comfort zone — most people don’t want change because change is uncomfortable” Griffin added.

Griffin also expressed concern for the students who will soon be entering middle and high school on the island.

“When they look at [students], they should see leaders — not people who are too scared to do anything,” Griffin said.

Additionally, Griffin stressed the importance of having faith in our community to make the necessary changes.

The efforts to address discrimination and bigotry must be an on-going process — there never has been and never will be an end-all “fix”.The response must be a result of District and school officials collaborating with and listening to the voices of those most impacted, namely students and Black, Indigenous, and individuals of color. Without broader input from students, and especially BIPOC voices, we cannot expect this cycle of bigotry and discrimination to end anytime soon.